By Lucie Laumonier*

There is no doubt that women were active participants in the world of artisanal production and retail in the later Middle Ages. The range of their activities was wide, their roles and rank varied, but overwhelming evidence shows that, everywhere, women were involved in trades. This article provides an overview of the roles and place of women in artisanal guilds in late medieval southern France, namely the Mediterranean coastal regions of Languedoc and Provence.

In towns and cities since the thirteenth century, artisanal work was framed by “statutes” of crafts, issued or sanctioned by the local governments, the local lords, or the Crown. Workers were structured in “guilds” or crafts locally described as confraternities, charities, or mestiers (giving us the modern French word, métier, for occupation or profession).

Woman ‘collecting cocoons of silk worms from trees and spin- ning the silk.’ France, N. (Rouen). Giovanni Boccaccio, De claris mulieribus – British Library MS Royal 16 G V, fol. 54v,

Bibliothèque nationale de France MS Latin 9333 fol. 43v

Bibliothèque nationale de France MS Latin 9333 fol. 61v

Masters were the highest-ranked workers of their trade. Until the late fifteenth century, in order to access that rank, workers had to own their own shop and be the head of their household. Women rarely earned the title of magistra, even when they had their own business, and hired employees and apprentices. About half of female employers, in Montpellier or in Marseille, were independent women, either unmarried or widows. The other half were married women who did not necessarily practice the same trade as their husband. In Montpellier between c.1300–1460, 8.5% of hiring contracts were concluded by an independent female employer, and 5.5% by a married couple, with the wife sharing the training responsibilities with her husband. Figures were lower in Marseille, with only 3% of independent mistresses in 1250–1400 work contracts studied by Francine Michaud.

A feature of female employers was that they tended to hire female employees and apprentices, and to support feminine work, as Kathryn Reyerson has shown in a recent study highlighting the importance of feminine networks of solidarity for women in trades.

As employees, women were quite rare in archival sources. Most of the surviving work contracts that involved young adults or adult women dealt with domestic service. In Marseille, among the more than 1,000 work and apprenticeship contracts, only five involved women employed in trades. Michaud notes that the majority of women and girls hired between c.1250–1400 would work as maids, wet-nurses, and other service-related occupations. Female employees were a little more numerous in Montpellier, but only represented 9% of the waged workers. They were usually poorly paid compared to male employees, hired for shorter periods of time and under more precarious terms.

This is especially true in the case of women employed in lower-status textile crafts and needlework. Women were employed in weaving, spinning and fine needlework, from Toulouse to Marseille, rather than in drapery and cloth making, the latter being more profitable and male-dominated industries. The 1279 statutes of the weavers and finishers of Toulouse suggested that all spinning was done by women. Some could work from home and supplement their household’s income with their meagre earnings. Sources show that women of the textile industry oftentimes hired female employees and trained young female apprentices.

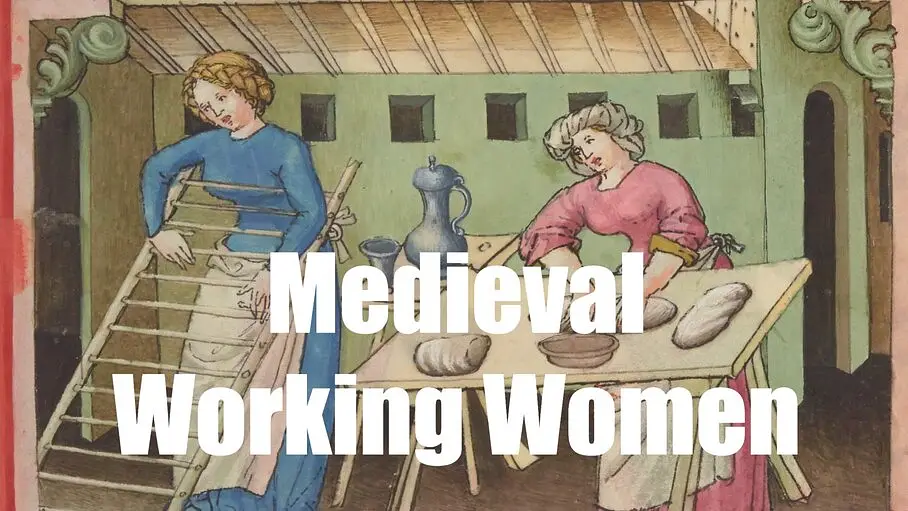

Besides the textile industry, food production and distribution was a common occupation for women, many of whom who worked as commodity retailers. The remarkable mid-fifteenth century manuscript of the Tacuinum Sanitatis housed at the Bibliothèque nationale de France contains several illustrations of women making and selling bread, filtering the flour, kneading the dough, and handing over the loaves to customers (MS Lat. 9333). Southern French sources confirm that many women did occupy prominent roles in the bakery and pastry-making business and that several girls were trained in the field. In the early 1340s in Marseille, the female baker Jeannette Barral obtained an important contract with the royal navy and promised to supply 2,000 quintals of sea biscuits within eight weeks. In Montpellier, administrative documents dated from c.1415 show female bakers pledging to respect the statutes of their profession.

Although largely underrepresented in work contracts, women from the South of France were employed in a wide range of occupations. They laboured on construction sites in Provence and Languedoc, often employed to do menial tasks, such as carrying bags of sand and buckets of water to make mortar. Some women were skilled in glassmaking and stained glass window making, or practiced the art of painting. In 1347 for instance, a girl named Guillemma was placed in an apprenticeship in Montpellier for four years to learn the art of painting from Alazacia, the widow of a ploughman, who was described as being a pictoressa (female painter). Women also laboured in professional areas that may seem less conventional, such as metalwork. In Alès, c.1425, a female cauldron maker was overseeing a family workshop which employed her daughter, son-in-law, niece and nephew-in-law; while in Montpellier a female blacksmith (fabressa) was found in fifteenth-century tax records.

Legal documents and work contracts only provide a glimpse of the involvement of women in the workforce. Many worked from and out of their house without a contract, while others participated in the familial workshop alongside their children with no wage.

The impact of the Black Death on women’s entry into the workforce and on their wages is still debated by historians. Some argue that more opportunities and higher wages became available to women in the aftermath of the first epidemic, which reached Marseille and Montpellier in 1348. Others contend that this rebound only stretched over two or three generations: in the fifteenth century, crafts started to exclude women from their ranks and fewer work contracts were found that involved women. Women did not disappear from the workforce in the fifteenth century, but their professional opportunities narrowed and they were pushed towards undeclared and more precarious employment.